Traditional African Medicine Review

This review focuses on ten traditional African medicine plants that can develop into future phytopharmaceuticals for treating and managing a wide range of chronic and infectious conditions. One of the most ancient and diverse therapeutic systems is traditional African medicine.

Traditional healers who prescribe traditional medicines to rural areas are often the best and most affordable option for local health care. They can also be the only treatment that exists. There is not yet a comprehensive update of traditional African medicinal plants.

We have used critical scientific databases to investigate trends in rapidly growing scientific publications about traditional African medicine. To increase the importance of traditional African medicine and plants, aspects like traditional use, phytochemical profile, in vitro, and clinical studies, have been investigated. Traditional African healers shall explore the future challenges concerning these plants.

Introduction To Traditional Medicine

Traditional African medicine refers to the totality of the knowledge, skills, and practices based on traditional beliefs and experiences from different cultures. Traditional African medicine treats and prevents mental and physical illnesses and improves and diagnoses them.

Complementary medicine or Alternative Medicine (CAM) is a form of traditional medicines that has been adopted outside its native culture by other people. According to the World Health Organization, 80% of emerging nations rely on traditional African medicine as a treatment.

The use of alternative medicine has increased in developed countries, especially herbal remedies, over the past decade. Herbal medicines are herbs, herbal materials, and herbal preparations. These herbal products may contain active ingredients or parts of plants. A majority of Ethiopia’s population uses herbal remedies as their primary healthcare.

However, studies in developed countries such as Canada and Germany show that 70% of those countries have used CAM or traditional medicines. Many generations passed on the deep knowledge of traditional African medicine, herbal remedies, and modern allopathic medicine, which is rooted in this ancient practice.

Many new vital remedies and traditional medicines will probably be developed from African biodiversity in the future, following the same path as the past, based on traditional practitioners, knowledge and experience. There’s a belief that the widespread use of traditional African medicine in Africa, mainly made up of medicinal plants, comes from both cultural and economic factors.

The World Health Organization (WHO) encourages African countries to integrate traditional African medicine practices into their health care services.

Secondary metabolites are phytochemicals found in indigenous plants. These phytochemicals can work together or independently to improve your health.

Contrary to many drugs, a medicinal plant may contain multiple chemicals that work together or in combination to create a more significant combined effect than their components. These herbal medicine substances can increase the activity of main medicinal constituents by accelerating or slowing down their assimilation into our bodies.

Secondary metabolites may be derived from plants and can increase the stability or potency of active compounds or phytochemicals. They also reduce unwanted side effects. The vast array of chemical structures found within these plants may not be waste products; instead, they could be secondary metabolites involved in the organism’s interaction and the environment.

These traditional medicines include signal products, repellants for pollinators, defense substances against predators and parasites, and resistance to pests and diseases. One traditional medicine plant might contain bitter substances that stimulate digestion, anti-inflammatory chemicals that reduce swellings, pain, and antioxidants.

Traditional medicines may also have antibacterial and antifungal compounds that act as natural antibiotics. Some traditional healers may consider using single phytochemicals to replace plant extracts to be a better option. However, after years of integrating traditional African medicine, scientific communities are now beginning to see the benefits of using standardized and crude extracts for medical purposes.

African Traditional Medicine

One of the oldest and best-known therapeutic systems, traditional African medicine is still used today. Africa is the birthplace of humanity, with its rich biological diversity and cultural diversity that includes regional variations in healing practices. Traditional African medicine is holistic and involves both the body and the mind in its many forms.

Traditional healers often diagnose and treat the psychological cause of an illness before prescribing medications, especially medicinal plants, to alleviate the symptoms. Two main reasons can explain the continued interest in traditional medicine within the African healthcare system.

First, there is a lack of access to western medical treatments and allopathic medicine. Most Africans cannot afford modern medical care because it is too expensive or not available. The second is a shortage of current treatment options for specific ailments, such as malaria or HIV/AIDS. These diseases are more prevalent in Africa than in any other country and significantly impact Africa.

Medicinal plants are the most famous traditional African medicine on the African continent. Many parts of Africa have medicinal plants as the best health resource, and they are also the most preferred choice for patients. Traditional healers provide information, counseling, treatment, and support to patients and their families.

They are also able to understand the patient’s environment. Africa has a wealth of biodiversity, and it is home to 5,000 medicinal species and a total of 45,000 plant species. It is no surprise that Africa is in subtropical and tropical climates.

Furthermore, it is well-known that medicinal plants naturally accumulate secondary metabolites to survive in hostile environments. Africa’s tropical climate means exposure to more ultraviolet radiation than the northern hemisphere, and this exposure could lead to African plants accumulating chemopreventive substances.

The documentation of traditional African medicine uses and traditional medical practices for their healing is becoming more critical due to the rapid loss of natural habitats due to anthropogenic activity and the erosion of valuable traditional knowledge. According to reports, Africa is home to 216 million hectares of forest. However, the continent is known for having one of the highest deforestation rates, at 1% per year.

The continent has the highest rate of biodiversity endemism, with Madagascar topping the list at 82%. It is also worth mentioning that Africa contributes almost 25% to the global trade in biodiversity. The paradox is that Africa has very few pharmaceuticals available for sale globally.

There are now more publications in scientific literature focusing on evaluating African medicinal plants. These plants are essential in maintaining health and introducing new treatments. However, there is no comprehensive update of traditional African medicine and herbal medicines. This review will highlight the importance and potential of African medicinal plants.

These plants and herbal medicines have both short- and long-term potential to develop future phytopharmaceuticals that can treat and manage a wide range of chronic and infectious conditions. This review may also serve as a basis for future research that aims to isolate, purify, and characterize bioactive compounds found in these plants and explore the potential niche market for these plants.

To investigate trends in rapidly growing scientific publications on African traditional medicine and medicinal plants, we used major databases like EBSCOhost and Scopus (Elsevier), Emerald, and Scopus (Elsevier).

Traditional medicines

We selected ten herbal medicine plants (Acacia Senegal, Artemisia Ferox, Artemisia herbal-alba, Aspalathus linearis, Centella Asiatica, and Catharanthus roseus) for detailed reviews based upon the following criteria:

- The African medicinal plants as part of the African herbal pharmacopeia.

The plants that produce modern phytopharmaceuticals.

Acacia senegal (L.) Willd. (Leguminosae: Mimosoideae)-Gum Arabic

Acacia Senegal, also known by gum Arabic, is a native of semidesert and drier areas in sub-Saharan Africa. It is widespread from Southern Africa to Northern Africa and used in North Nigeria, West Africa, and North Africa as a medicine plant.

Gum arabic, also known as gum acacia, derives from bark exudates and dates back to the first Egyptian Dynasty (3400 BC). It was used in ink production using a mixture of water, carbon, and gum. This gum is called “komi” in 18th Dynasty inscriptions used for over 4,000 years in ink manufacture.

A mixture of water, carbon, and gum made the ink. A. Senegal’s gum has been used for centuries by traditional health practitioners to treat various infections, including bleeding, bronchitis and diarrhea, gonorrhea, and typhoid fever. Traditional healers use gum acacia to bind pills and stabilize emulsions.

Acacia Senegal can also be used in aromatherapy to apply essential oils. A. Senegal, a natural oil-in-water emulsifier that is important in both the food and pharmaceutical industries, is currently in widespread use.

Gum arabic is a crucial food additive that the Codex Alimentarius has approved as safe for toxicological use. It helps in skin protection, demulcent, and pharmaceutical aids, such as stabilizers, emulsifiers, and additives for solid formulations.

Traditional healers can also use it to treat fungal and bacterial infections of the skin and lips. It is said to soothe the mucous membranes in the intestines and relieve skin inflammation. Internally it reduces inflammation in the intestinal mucosa and externally to cover inflamed areas such as burns, sore nails, and nodular lesions.

It is an expectorant, astringent, and catarrh used against colds and coughs, diarrhea, bleeding, sore throat, and typhoid. A. Senegal’s gum is used pharmaceutically mainly to produce emulsions, make pills and troches (as an excipient), and as a masking agent for acrid-tasting substances like capsicum and as a film-forming ingredient in peel-off masks.

Gum arabic works in food products such as soft drinks and candies, and it is safe to eat, as it has the same properties as glue. Gum acacia exists in many organic products as a natural alternative to chemical binding agents. Gum acacia commercially emulsifies beverages and manufactures flavor concentrates.

Traditional Health Practitioners Research

Recent reports have shown that traditional health practitioners and their researchers tested A. Senegal bark extracts in vitro for antimicrobial activity against human pathogens (Escherichia Coli, Staphylococcus Aureus, Streptococcus pneumonitis, Klebsiella pneumonia, and Shigella dysenteriae).

Traditional healers and researchers discovered that the extract had significant antibacterial properties, which was likely due to tannins and saponins within the plant. In vitro cytotoxicity testing showed that the section of the plant might not be toxic to humans.

Aloe Ferox Mill. (Xanthorrhoeaceae)-Bitter Aloe or Cape Aloe

Aloe Ferox is a native of African countries like South Africa and Lesotho, and it is the most popular Aloe species in South Africa. Aloe Ferox is a plant used as an alternative medicine since the beginning of time, and it has been well documented and is one of few plants depicted in San rock painting.

The bitter aloe vera, also known as Cape Aloe, is used in Africa and Europe as a laxative medicine. It possesses bitter tonic, anti-inflammatory, and antimicrobial properties. A. Ferox has been used as a traditional medicine in many commercial applications.

The pharmaceutical and natural food industries highly value it. A. Ferox, South Africa’s most widely traded wild-harvested species, is a vital component of the country’s economy. Aloe bitters are the final product of aloe taping and have been a significant export product of South Africa since 1761, when the country first exported it to Europe.

Many rural communities depend on the aloe tapping industry for their livelihood. The country created trade agreements and cooperatives to formalize the industry. There has been speculation that aloe tapping may have a significant poverty alleviation impact in Africa.

A. Ferox is known for its many medicinal and traditional uses. A. Ferox is frequently used to relieve constipation, and people apply the oil to their skin and mucous membranes. Scientific research supports these traditional uses. A. Ferox has been gaining popularity in the cosmetics industry.

According to reports, A. Ferox gel has at least 130 medicinal ingredients with anti-inflammatory and calming effects. It includes antiviral, antiparasitic, and antitumor effects. A Ferox contains a wide variety of phenolic compounds (chromones, anthraquinones, anthrone, anthrone-C-glycosides, and other phenolic compounds), and these compounds are well-documented to have biological activity.

Researchers and traditional healers have identified its arabinogalactan- and rhamnogalacturonan gel polysaccharides. It is still unknown what the composition of leaf gel is and what its biological activities are. Aloin, also known as Barbaloin, is the active ingredient (or purgative principle). It is also rich in antioxidants, indoles, and alkaloids.

Most total polyphenols in the gel are nonflavonoid. Tests have shown that this phytochemical profile in the A. Ferox leaf gel effectively relieves non-communicable diseases like cancer and cardiovascular disease, neurodegeneration, diabetes, and other chronic conditions.

The leaves contain two juices. The bitter yellow sap is used to lax the stomach, while the white aloe vera gel works in skincare products and health drinks. This purgative drug treats stomach problems.

It can work as a laxative to “purify” and as a bitter tonic (amarum) in various digestives or stomachics (such as “Lewensessens” and “Swedish Bitters”). A small amount of the drug, usually between 0.05 and 0.2 g, is taken orally as an appetite suppressant.

For arthritis, people may use half the recommended laxative dose. Fresh bitter sap treats conjunctivitis, sinusitis, and other conditions. It is well-known that bitter substances can stimulate gastric juice flow and improve digestion.

Traditional health practitioners can also treat burn wounds with fresh juice from the leaf. A. Ferox can heal burn-wounds by promoting tissue growth (granulation). Aloins enriched in A. Ferox can inhibit collagenase activity and metalloprotease activity, leading to the degradation of collagen connective tissue.

In an animal model, researchers tested the safety of A. Ferox whole-leaf juice, and they found the leaf juice to positively affect skin healing and repair. The A. Ferox whole-leaf juice preparation speeds wound healing and inhibit microbial growth. There was no dermal toxicity or side effects during the experiment.

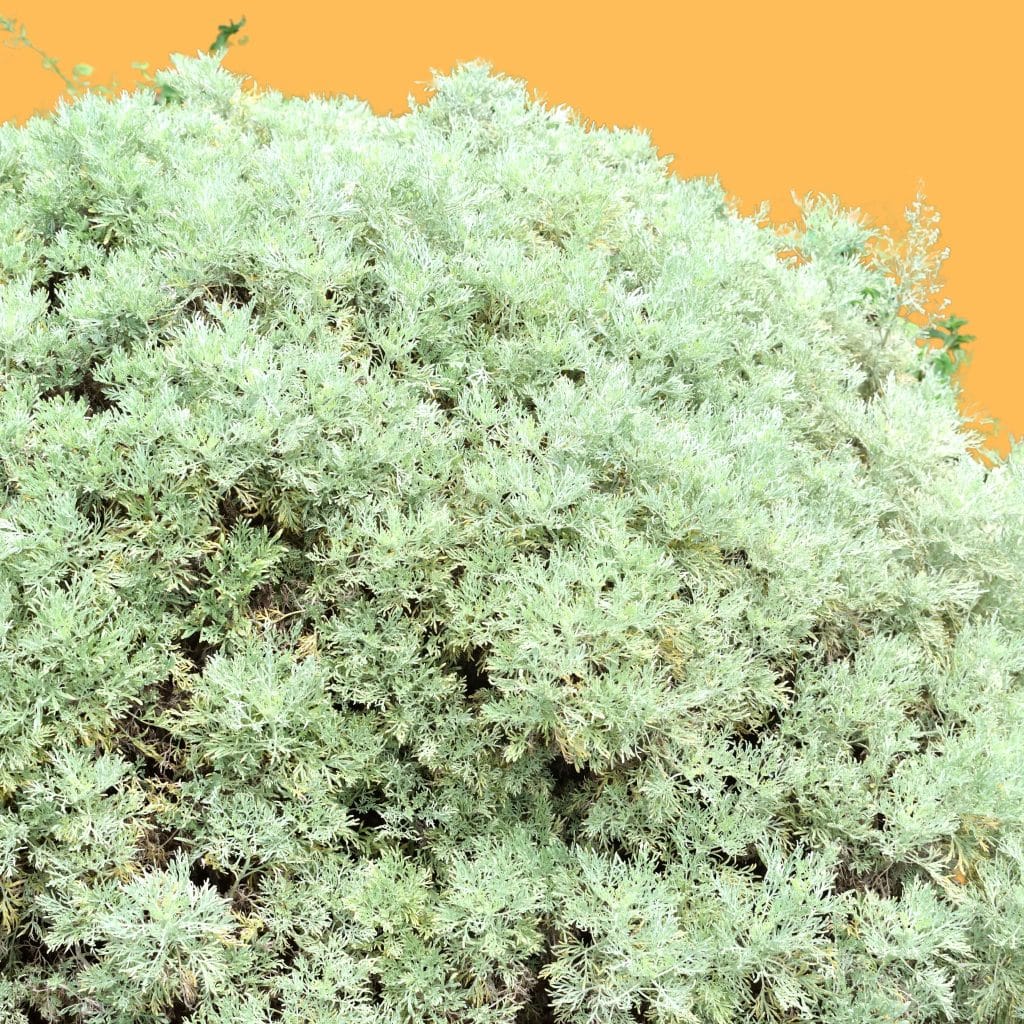

Artemisia herb-alba Asso (Med) Asteraceae-Wormwood

Artemisia herb–alba is also known as desert wormwood, Shih in Arabic, and Armoise Blanche (French). It is a perennial dwarf shrub with an intense aromatic greyish color native to Western Asia, the Arabian Peninsula, and Northern African countries. Many cultures have used A. herbaalba in folk medicine since ancient times.

Moroccan traditional healers use it in alternative medicine to treat arterial hypertension. In Tunisia, traditional African healers use it to treat hypertension and diabetic bronchitis. The herbal tea made from A. herb alba works as an analgesic and antibacterial agent in herbal medicine.

An ethnopharmacological survey among Bedouins in the Negev desert revealed that they used A. herb alba to treat stomach disorders. This plant works as fodder for sheep and livestock in the Algarve plateau region, where it is abundant.

Traditional healers reported the oil of the Libyan A. herb alba to have killed Ascaridae in short order. The oral administration of 0.39g/kg of A. herb–alba’s aqueous barks or leaves shows to result in a significant drop in blood glucose levels.

However, the aqueous root extract and the methanolic extract from the aerial parts of A. herb–alba do not cause any reduction in blood glucose levels. The LD50 value of the extract from the aerial parts of A. herb-alba seems to be low and appears to have no adverse effects.

Essential oils are among the A. herb–alba phytochemical components. Researchers and traditional healers have identified several chemotypes. Dob and Benabdelkader revised the variability of essential oils from A. herb alba from Spain, Israel, and Morocco.

However, many other traditional medicine studies have confirmed its high chemical polymorphism. Recent traditional medicines research identified fifty components in A. herb-alba oils. The oxygen-containing monoterpenes were dominant in all cases (72-88%). Camphor was the major component of the oil with (17-33%), an-thujone (7-28%), and chrysanthenone (1-49%).

Three types of oils can be identified despite the similarities in their main components: (a) A-thujone: camphor (23-28: 17-28%),(b) Camphor: Chrysanthenone (33.3 % 12%), and (c), A-thujone: camphor: chrysanthenone (24-43%].

Traditional Health Practitioners Artemisia Research

Researchers and traditional healers linked Artemisia herb alba’s antifungal activity to two volatile compounds found in the fresh leaves. They found Artemisia herb alba to contain piperine and carvone.

The antifungal activity for the purified compounds piperitone and carvone was determined to be 5 mg/mL, 2 mg/ml, and 1.5 mg/mL, respectively, against Penicillium citrophthora and Mucor rouxii.

Another traditional medicine study reported the antifungal activity and biological activities of Artemisia herbal essential oils from 25 Moroccan medicinal plants, including A. herma-alba against Penicillium digitatum and Phytophthora citrophthora.

Aspalathus linearis, Brum. f. R. Dahlgren. (Fabaceae)-Rooibos

Aspalathus linearis is an endemic South African fynbos tree that makes the well-known herbal rooibos tea. Its popularity and acceptance worldwide have been due to its caffeine-free status and relatively low tannin content. Rooibos works in various products, including extracts for beverages, food, nutraceuticals, and cosmetics.

Traditional healers use Rooibos in many different ways across Africa, and it can be used as a refreshing beverage or as a herbal tea. After discovering that rooibos infusions could help treat colicky babies with chronic restlessness, nausea, vomiting, and stomach cramps, it gained a broader consumer base.

Since then, many babies have been fed Rooibos as an infusion to their milk or as a soft beverage. Animal research has shown that the plant can produce powerful antioxidants, immunomodulating and chemopreventive properties. It is high in minerals and has low levels of tannins.

C-glucoside dihydrochalcones are unique flavonoids found in the plant, with nothofagin being the most common and aspalathin the least. Although researchers have not conducted clinical trials, in vitro data suggests that daily intakes of alkaline extracts from red rooibos tea may effectively suppress HIV infection.

The evidence is mounting that flavonoids in the tea contribute significantly to preventing cardiovascular disease and other diseases associated with aging. Recent research has shown that aspalathin can positively affect Type 2 diabetes glucose homeostasis by stimulating glucose uptake and insulin secretion in pancreatic beta cells.

Unfermented Rooibos has more chemoprotective properties than the fermented version. Aspalathin is free-radical capturing, and the body absorbs it via the small intestine. In vitro and in vivo, Rooibos shows antispasmodic, bronchodilator, and blood pressure-lowering properties.

The antispasmodic effects of rooibos tea were confirmed to be mediated primarily by potassium ion channel activation. Evidence is growing that Rooibos may have antimutagenic properties. Research in animals suggests that Rooibos can prevent lipid peroxidases from accumulating in the brain with age.

Due to its lack of alkaloids, and low tannin content, Rooibos has grown in popularity in Western countries. Rooibos also contains high levels of antioxidants like nothofagin and aspalathin. Water-soluble polyphenols like quercetin and rutin confer an anti-oxidative effect.

Rooibos helps with nervous tension, allergies, digestive problems, and other issues. Although these products are considered dietary supplements, people can purchase Rooibos extracts in pills.

Recent herbal medicine research has highlighted the potential of aspalathin and selected rooibos extractions such as an aspalathin enriched green rooibos oil extract as anti-diabetic agents.

Traditional Medicines in Japan

Japan filed a patent application to use aspalathin within this context. It also filed a placebo-controlled trial application to use Rooibos as an anti-diabetic agent.

The claims are that rooibos extract, and a hetero-dimer containing Rooibos can treat neurological and psychiatric disorders in the central nervous system. Another avenue of opportunity may be with topical skin products. Two studies have supported the topical application of rooibos oil extract.

The traditional medicine studies examined the inhibition of COX-2 expression in mouse skin and the inhibition of skin tumor growth promotion in mice. However, further herbal medicine research is needed to determine its potential for preventing skin cancer in humans.

Centella asiatica (L.) Urb. (Apiaceae)-Centella

Centella Asiatica is a medicinal plant used since prehistoric times. It is found worldwide and used in many traditional healing practices, such as Ayurvedic medicine and Chinese traditional medicine. It still works in folk and traditional medicine.

However, it is becoming more common to find itself at the intersection of modern science-oriented medicine and traditional medicine. C.asiatica has been used traditionally for wound healing, burns, ulcers, leprosy, and tuberculosis.

It also treats syphilis and epilepsy. C.asiatica was first used in Mauritius to treat leprosy in 1852. Clinically using C.asiatica as a therapeutic agent for treating leprous lesions dates back to 1887.

Clinical effects of the active constituents include wound healing, chronic venous disease, cognitive function, and wound healing. Thorough herbal medicines research led to the discovery that C.asiatica contains several pentacyclic triterpenoids.

Asiaticoside and madecassoside represent the most important active compounds used in drug preparations. A traditional healer uses them commercially primarily as wound-healing agents due to their anti-inflammatory properties.

C.asiatica’s main active component is the triterpene saponin of the ursane type, asiaticoside. It is responsible for wound healing. It is also known to stimulate type-1 collagen synthesis in fibroblasts cells.

Asiaticoside Studies in Several Countries

Asiaticoside concentrations have varied between 0.006 and 6.42% in plants collected from India, Madagascar, the Andaman Islands, and South Africa. C. Asiatica also has several triterpene-saponins. Madecassoside is a co-occurring compound with asiaticoside. Other saponins, such as centelloside, asiaticoside A to G, and brahmoside have also been reported.

Madagascar is a crucial player in the C.asiatica trade, and Malagasy is the world’s first producer of C.asiatica products. The industry appreciates Malagasy origin because of its higher Asiaticoside contents in dried leaves.

Herbal medicines research has shown that the C.asiatica ethyl-acetate fraction increases the i.p. effect. Gabapentin, phenytoin and valproate were administered to antiepileptic drugs. They also decreased the incidence of pentylenetetrazol (PTZ)-induced seizures in rats.

Chatterjee and colleagues reported that the extract might affect the levels of gamma-aminobutyric acids (GABA), which could explain this result. Ramanathan and colleagues investigated the neuroprotective effects of the plant on monosodium glutamate-treated rats.

C.asiatica extracts protected the general behavior, locomotor activity, and the CA1 area of the hippocampus. C. Asiatica extracts showed neuroprotective properties. The superoxide dismutase and catalase levels in the striatum and hippocampus were higher.

A double-blind, placebo-controlled study surveyed 28 healthy older participants to determine the effects of C.asiatica on cognitive function. Cognitive performance and mood modulation were evaluated in the subjects who received C. Asiatica at different doses available, from 250mg to 500mg and 750mg each day for two months.

The high dosage of the extract increased by working memory and greater amplitude of N100 event-related potential. The C.asiatica treatment also led to improvements in self-rated mood.

After 1 to 2 months, researchers found the high dose of C.asiatica used in this study to increase alertness and calmness. The exact mechanism behind these effects requires further research.

Catharanthus roseus (L.) G. Don (Apocynaceae)-Madagascan Periwinkle

Catharanthus roseus (Madagascar periwinkle) is a well-known African medicinal plant. This species is a source of anticancer alkaloids vincristine (and vinblastine), whose complexity makes them challenging to synthesize in the laboratory—the only source for these species’ leaves today.

C. roseus is a native of Madagascar, but it has spread widely throughout the tropics. Researchers can trace the story of the traditional use of this plant back to Madagascar, where healers used it extensively to treat a variety of ailments.

C. roseus is used as a bitter tonic and galactagogue in traditional medicine. It treats rheumatism and skin disorders as well as venereal diseases. C. roseus is rich in phytochemicals, with as many as 130 components.

Vindoline is the main component (up to 0.5%). Other biologically active compounds include serpentine, catharanthine, ajmalicine raubasine, akuammine lochnerine, lochnericine, and tetrahydroalstonine.

The medicinal plant is also rich in bisindole alkaloids; vindoline and catharanthine appear in tiny amounts: vincristine (=leurocristine) in up to 3 g/t of dried drug and vinblastine (=vincaleucoblastine) in a slightly more significant piece.

In normal rats, oral administration of water-soluble fractions of ethanolic extracts from the leaves resulted in significant dose-dependent decreases in blood sugar levels at 4 hours by 26.2, 31.4, and 35.6, respectively.

Additionally, in rats, 500 mg/kg oral administration 3.5 hours before oral glucose tolerance test (10mg/kg) and 72 hours after STZ administration (50mg/kg IP) had significant antihyperglycaemic results.

There were no gross behavioral changes or toxic effects above 4 mg/kg IP. Orally administered 500 mg/kg of extract for 7 and 15 days, the results showed 48.6 and 57% hypoglycemic activity, respectively.

The same 30-day treatment protected against the streptozotocin challenge (75 mg/kg/i.p.). X 1. Enzymatic glycogen synthase, glucose 6-phosphate-dehydrogenase, succinate dehydrogenase, and malate dehydrogenase decreased in the liver of diabetic animals compared to normal ones.

These significantly improved after treatment with extract at a dose of 500 mg/kg p.o. for seven days. The results showed that the rats were more likely to metabolize glucose.

Treatment with the extract also reduced lipid peroxidation levels in diabetic rats, as measured by 2-thiobarbituric acid reactive substances. Vincristine, Vinblastine and Vinblastine act as antimitotics.

They bind to tubulin and stop the formation of microtubules, which aid in constructing and maintaining the mitotic spindle. This binding blocks mitosis in metaphase.

Both these alkaloids have high levels of toxicity. Vincristine and vinblastine are particularly toxic because they interfere with neurotransmission.

They have peripheral neurotoxic effects such as neuralgia and paresthesia. Their significant neurotoxic effects include convulsive episodes, respiratory difficulties, and loss of tendon reflexes.

A few side effects are Alopecia digestive distress, including constipation, ulcerations in the mouth, amenorrhoea, and azoospermia. Recent reports have reported new phenolics found in various plant parts (leaves and stems, seeds, and petals), including flavonoids and phenolic acid.

Traditional medicine researchers also did a phytochemical study on several classes of metabolites, and they evaluated their bioactivity. C. roseus’ high antioxidant potential shows in vitro using superoxide, DPPH, and nitric dioxide.

Cyclopia genistoides (L.) Vent. (Fabaceae)-Honeybush

Cyclopia Genistoides, an indigenous South African herbal tea, is considered healthy. Traditional tea preparation involves the fermentation of leaves and flowers and their drying.

It also has positive effects on the bladder. Because it does not contain harmful substances like caffeine, it works as a substitute for tea. It is one of few South African indigenous plants to have transitioned from a wild plant to a commercial product in the last 100 years.

The past 20 years of herbal medicine research have focused on propagation, production, and genetic improvement. Honeybush decoctions treat chronic catarrh, pulmonary tuberculosis, and other conditions. Honeybush infusions are said to increase appetite.

However, no information is available about the species. Marloth says Honeybush is a healthy and nutritious food, and it aids in weak digestion but does not have any stimulating effects on the heart. Honeybush can also relieve heartburn and nausea.

It stimulates breastfeeding mothers’ milk production and treats colic in babies. Honeybush can be used as an infusion or mixed with Rooibos, and Teabags often contain more Rooibos than Honeybush.

People also combine Honeybush with parts of other South African plants and fruit, such as dried buchu leaves and pieces of African potato (Hypoxis hemerocallidea), corms, or dried marula (Sclerocarya birrea).

Honeybush “espresso” is still not available in the ready-to-drink form. Honeybush tea is a health-promoting herbal tea that is caffeine-free and low in tannin. Although the same bioactive phytochemicals of Honeybush are not known, their beneficial effects are attributable to phenolic compounds.

All species analyzed have found the xanthones mangiferin (and isomangiferin) and the flavanone hesperidin. Two benzophenone derivatives, 3-C-glucosides maclurin (and iriflophenone), were recently isolated from C.genistoides.

Herbal medicines researchers tested for their pro-apoptotic activities toward synovial fibrils in patients with rheumatoidarthritis. Iriflophenone 3-Cb-glucoside and isomangiferin had the most vigorous pro-apoptotic activities.

Previously, researchers did not consider these compounds as possible antiarthritic agents. Mangiferin, a primary polyphenol in honeybush plants, has pro-apoptotic activity.

C. genistoides is a new antioxidant product that contains high amounts of mangiferin. C. genistoides is a popular source of mangiferin due to its sustainability and the latter. Other potential uses for C. genistoides include preventing skin cancer and relieving menopausal symptoms.

Harpagophytum procumbens (Burch.) DC. (Pedaliaceae)-Devil's Claw

Harpagophytum Procumbens is a native of the Transvaal in South Africa, Botswana, and Namibia, and now it is found in the Kalahari and Savannah desert regions. Since ancient times, the indigenous San and Khoi peoples in Southern Africa have used Devil’s Claw to treat their ailments.

Harpagophytum Procumbens is an ancient African medicine with multiple uses. It is exported to Europe in bulk for use in various health products, including teas, tablets and capsules, and topical gels and patches.

Analgesia and anorexia traditionally work as analgesic and anti-inflammatory in joint disorders, back pain, headaches, and other conditions. Scientific studies on animals and humans have shown that the standard Devil’s claw is a mild analgesic to joint pain in Europe.

Chemical constituents according to the published literature include potentially (co)active chemical constituents: iridoid glycosides (2.2% total weight) harpagoside (0.5-1.6%), 8-p-coumaroyl harpagide, 8-feruloyl-harpagide, 8-cinnamoylmyoporoside, pagoside, acteoside, isoacteoside, 6′-O-acetylacteoside, 2,6-diacetyl acteoside, cinnamic acid, caffeic acid, procumbide, and procumboside. H. procumbens has the 6-acetylacteoside component, which is absent in H. zeyheri.

It allows users to differentiate between the two species. Flavonoids, flavonoids, and aromatic acids are also present. The concentration of harpagoside from H. procumbens is variable within the plant. It is highest in secondary tubers and lowers in primary roots.

Active compounds are absent from the flowers, stems, leaves, and stems. Iridoid and phenylbutazone-like effects exist in H. procumbens’ iridoid glycosides. They appear to be dose-dependently anti-inflammatory, analgesic, and pain-killing. Harpagoside is most effective when administered parenterally, but it loses its potency when taken by mouth. Enteric-coated preparations may still be adequate despite being exposed to gastric acid.

Harpagoside inhibits arachidonic acid metabolism via both the cyclooxygenase and lipoxygenase pathways. Many opinions and divergences regarding Devil’s paw’s analgesic and anti-inflammatory effects in treating low back pain and arthritic conditions.

It is unclear what the active ingredient of Devil’s claw is and how it works, and this mechanism appears distinct from nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) mechanisms. Based on scientific evidence in animals and humans, the standard Devil’s claw works in Europe as a mild painkiller for joint pain.

Herbal medicines researchers have conducted multiple clinical studies to assess the effectiveness of H.procumbens as an anti-inflammatory, general painkiller (commonly used for lower back pain), and anti-rheumatic drug.

Alternative medicine researchers gave Harpagophytum extract W1351 in two daily doses, 600 mg and 1200 mg, containing 50 mg and 100 mg of harpagoside. It was compared with a placebo to determine its effectiveness for lower back pain.

Researchers conducted a double-blind, randomized study over four weeks. Subjects suffering from chronic back pain or current exacerbations of intense pain were eligible for the study.

Six of the 183 participants in the trial reported that they felt pain-free without Tramadol (rescue medication for pain). Data analysis showed that the 600 mg group had more benefits in areas with less severe pain, no radiation, or neurological deficit.

Patients with severe pain tended to take more Tramadol, but not the maximum allowed dose.

Momordica charantia Linn. (Cucurbitaceae)-Bitter Melon

Momordica Charantia, a tropical vegetable found throughout Africa, is also known as bitter melon. The leaves make a tea called “cerassie,” and the juice from the different parts of the plant (fruit pulp, seeds, and leaves) is a standard folklore treatment for diabetes.

M. charantia is a well-known folklore hypoglycemic herb. The plant extract has been called vegetable insulin. M. charantia contains several active compounds, subject to mechanistic research.

Galactose binding protein lectin, with a molecular mass of 124,000, was isolated from M. charantia’s seeds and compared to insulin for its antilipolytic and lipogenic properties in isolated rat pancreatic cells.

Several animal models have observed Hypoglycemic effects using extracts from fruit pulp, seeds, leaves, whole plants, and whole plants of M. Charantia. Fresh and frozen M. charantia significantly improved glucose tolerance in standard and diabetic rats.

Hypothesized M. charantia fruits may contain more than one type of hypoglycemic ingredient. These may include an active principle called “charantin,” a homogenous mixture of b-sitosterol-glucoside and 2-5-stigmatadien-3-b-ol-glucoside that can produce a hypoglycemic effect in normal rabbits.

They found that blood glucose levels had dropped by 22% in ninety minutes. The liver’s glucogenic enzymes-glucose-6-phosphatase and fructose 1, 6-bisphosphatase were also depressed.

Another evidence of a positive chronic effect is observing an improvement in glucose tolerance and fasting glucose levels in 8 NIDDM patients after seven weeks of daily intake of powered M.charantia fruit.

Welihinda and colleagues. have disputed the assertion that M. charantia causes an increase in insulin levels. Welihinda showed that an aqueous extract of M.charantia stimulated insulin release in pancreatic islets from obese-hyperglycaemic mice.

Recently, Matsuura et al. isolated a glucosidase inhibitor in M. charantia plants, a drug therapy for high postprandial glucose (PPHG). Methanol, saline, and saline extracts prevented adrenaline-induced hyperglycemia.

When tested on laboratory animals, researchers found bitter melon to be hypoglycemic and antihyperglycaemic. Subcutaneous administration to humans, langurs, and gerbils of polypeptide-p, derived from bitter melon fruit, seeds, and tissue, showed powerful hypoglycaemic results.

M. charantia aqueous extracts improved oral glucose tolerance tests (OGTT) in normal mice after eight hours and decreased hyperglycemia by half in STZ diabetic mice after five hours.

Chronic oral administration of M. charantia extract to normal mice for 13 consecutive days improved OGTT, but no significant change in plasma insulin levels. Recent research has shown that M.charantia fruit extracts can have an in vitro effect on glucose transport.

Pelargonium sidoides DC. (Geraniaceae)-Umckaloabo

The coastal region of South Africa is home to Pelargonium sidoides. Available ethnobotanical data shows that the tuberous P. Sidoides is a traditional medicine with a rich ethnobotanical past.

The herbal remedy Umckaloabo (P. sidoides root extract, also known as Umckaloabo, effectively treats acute respiratory infections. Researchers have done numerous studies on P. sidoides concerning respiratory tract infections.

Although these African traditional medicine studies suggested that P. sidoides might effectively relieve symptoms of acute rhinosinusitis in children and adults, doubt remains.

It may effectively alleviate symptoms of acute bronchitis, both in children and adults, and sinusitis in adults. EPs 7630 significantly decreased bronchitis symptoms scores in patients suffering from acute bronchitis within seven days.

The study has no reports of severe adverse reactions received. EPs 7630 exerts a positive influence on phagocytosis and intracellular killing of cells. Extracts of P. sidoides modulate the secretory immunoglobulin-A production in saliva and interleukin-6 and interleukin-15 levels in the nasal mucosa.

One study found that P. sidoides effectively treat common cold symptoms and speed up recovery time in common cold patients. These effects led the authors to determine if P. sidoides might affect asthma attacks following upper respiratory tract viral infections.

There have been 20 published clinical trials results. Seven of those were observational, and thirteen were double-blind and placebo-controlled. For 6 of the 13 trials, researchers only published preliminary results.

They conducted all trials using EPs 7630 in either liquid or solid form. Two reviews have analyzed this data. Kayser evaluated the antibacterial activity of P. sidoides extracts and isolated components against five gram-negative and three gram-positive bacteria.

Kayser found that most compounds had antibacterial properties. Lewis and colleagues did further research and confirmed these findings.

The synergistic indirect antibacterial effect of EPs 7630 in group A-streptococci has been demonstrated by inhibiting bacterial adhesion in human epithelial cells and inducing bacterial adhesion in buccal epithelial cells.

Herbal medicines research has shown Umckaloabo stimulates intracellular killing, phagocytosis, and oxidative burst. The modulation of epithelial cell bacteria interaction via EPs 7630 could protect mucous membranes against microorganisms that evade host defense mechanisms.

These results tend to support the use of EPs 7630 in upper respiratory tract infections. Recently, researchers established antimycobacterial activity for hexane extracted roots of P. sidoides and P. reniforme. Goedecke et al. Godecke et al.

Indirect stimulation of the immune response may have an antitubercular effect. Mativandlela and colleagues supported this assumption because none of the compounds from P. sidoides had any significant activity against M. tuberculosis.

Kayser et al. using bioassays, investigated the effects of P. sidoides extracts and constituents on non-specific immune functions. They discovered indirect activity through activation of macrophage functions.

The presence of TNF-alpha and inorganic Nitric Oxides (iNO) confirmed activation. Kolodziej also found TNF-inducing potentials for EPs 7630 and interferon-like activity.

Koch et al. investigated polyphenol-containing extracts of P. sidoides and simple phenols, flavan-3-ols, proanthocyanidins, and hydrolyzable tannins for gene expressions (iNOS, IL-1, IL-10, IL-12, IL-18, TNF-alpha, and IFN-alpha/gamma). All compounds and extracts could increase cytokine mRNA levels and iNOS in parasitized cells.

Discussion

Since time immemorial, traditional African medicine and plants have been integral to the African healthcare system. Traditional African herbal medicine is popular because it is part of African medical practice.

It also has an economic advantage. On the one hand, it is not affordable for the poor, while on the other, the wealth and diversity of Africa’s fauna and flora are a source of treatments for a wide range of ailments.

However, clinical evidence is lacking to prove that this traditional African medicine is safe and effective for medical practice in humans. Despite this, traditional African medicinal plants users remain skeptical about their effectiveness.

This skepticism makes it difficult for people to choose cheaper and more easily accessible plants. People must also consider the safety of herbal remedies. Information about the safety and efficacy of traditional African medicine is crucial.

This paper focuses on a small number of traditional African medicine and plants that can be used as phytopharmaceuticals in the future to manage chronic and infectious conditions.

To increase the importance of traditional African medicine, we have examined aspects like traditional use, phytochemical composition, in vitro, in-vivo and clinical studies related to their use.

It has been clear that many plants have had medicinal potential over the past few decades, and many have been used in western medicine. It is increasingly becoming accepted that traditional African medicine and plants may offer potential templates for Western medicine and drug discovery molecules.

Many of these medicinal plants have promising medicinal properties that can be used in western medicine and warrant further clinical research. Despite their favorable medicinal properties, not all have substantial scientific and clinical evidence.

Alternative medicine also has a niche market (e.g., Aloe ferox and Artemisia afra and Aspalathus linearis and Centella Asiatica) that needs to be further explored and proven before they are available on the global market.

Modern science has made it possible to identify and characterize bioactive components of these plants. The medically challenging task of discovering therapeutic compounds from traditional African medicine and plant remedies is still significant.

Developing robust and reproducible bioassays is necessary given our limited knowledge of multifactorial disease pathogenicity. Innovative strategies are required to improve the collection process, especially when considering the legal and political implications of benefit-sharing agreements.

Because drug discovery from medicinal plants is time-consuming, investigators need to develop new automated bioassays. Automation will allow them to screen, isolate and process data quickly for product development.

These procedures should also rule out false-positive hits and deplication methods to eliminate nuisance compounds. Even though traditional African medicine has been subject to a systematic and method-oriented evaluation, there is still little literature on the topic compared to western medicine.

Information about the best practices for quality control, authentication, and standardization needs improvement. Proper raw material management, extraction processes, and final product formulation could lead to appropriate standardization.

Ineffective quality control can lead to inconsistent product quality and lower market value. The lack of quality control standards and technical specifications and lack of validation of traditional knowledge are significant obstacles to developing an African phytomedicine industry.

It is challenging for buyers to compare products and batches from different countries or year to year and assess safety and efficacy. This challenge contrasts starkly with Europe and Asia, where traditional methods and formulations get documented and evaluated locally and nationally.

This difference could also explain why phytomedicines are more prevalent in Europe and Asia than Africa. It is crucial that any potential risks, such as the contamination of medicinal plants with heavy metals from traditional African medicine, be addressed.

Africa should develop and enforce regulatory guidelines. It is essential to control medicinal plants’ growth under GACP and maintain a clean environment (under Good Manufacturing Practice).

Cultivated plant material is preferable for the medicinal plant industry because it is easier to manage the supply chain with minimal contamination. However, it is essential to identify the source of the therapeutic plant material to ensure quality control.

After this, any potential human pathogens, such as fungus and bacteria, must be identified and checked at each processing stage. The material’s bioactive properties will be certified by chemical, pharmacological and toxicological tests, according to Good Laboratory Practices (GLPs).

These tests are also a predictor of the safety of the manufactured products. Researchers must prove clinical safety and efficacy in the initial stages of developing a therapeutic agent through extensive and often lengthy trials.

Producing the unit dosage forms according to the established operating procedures will ensure safety. Africa should establish quality assurance procedures to ensure that products from factories are safe, effective, and of high quality.

This quality assurance is why product standardization and double-blind placebo-controlled and randomized clinical controlled studies using standardized products or products that contain pure plant extracts are crucial components of the development phase.

Conclusion

The literature shows a renewed interest in plant-based traditional African medicine treating various diseases. The role of medicinal plants in the healthcare system of African countries is still essential.

African countries must overcome numerous obstacles to achieve their full potential. The effectiveness of herbal medicines for treating diseases still needs full validation using robust scientific criteria, making it difficult to compare with conventional treatments.

Other issues to be addressed include access and benefit sharing in the Nagoya Agreement. If the trade between traditional African medicine and products is to grow, local laws must be TRIPS-compliant.

At the same time, authorities must address sustainable use and development issues of plant products.